Science

Rethinking Intelligence: Contextual Applications of Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences in Education

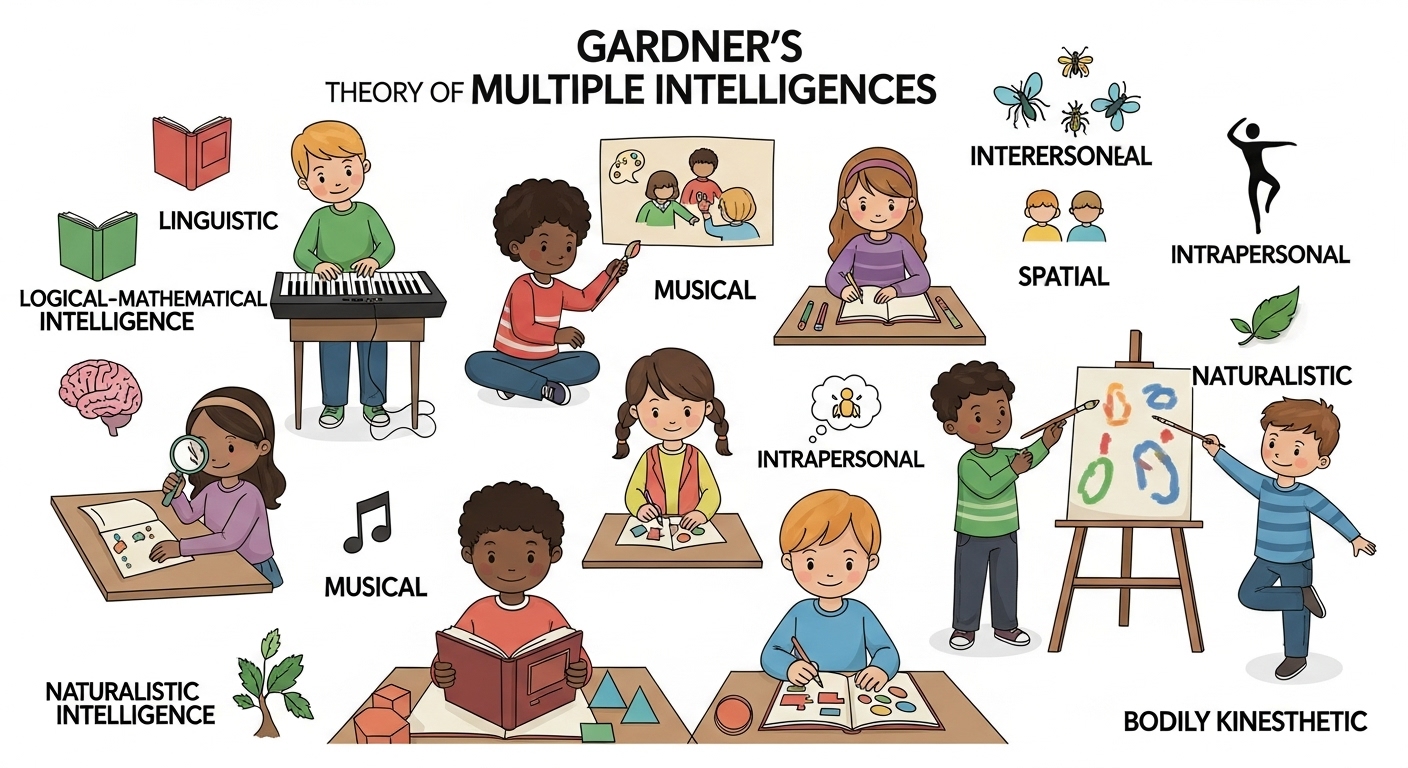

For decades, intelligence has been narrowly defined through standardized testing and IQ scores, often privileging linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities. While such measures have predictive value for certain academic outcomes, they fail to capture the diversity of human capabilities visible in classrooms, workplaces, and everyday life. In response to this limitation, psychologist Howard Gardner introduced the Theory of Multiple Intelligences (MI), proposing that intelligence is not a single, unitary construct but a constellation of distinct yet interacting capacities.

Although Gardner’s theory remains controversial within cognitive psychology, it has had a profound and lasting impact on educational practice worldwide. This blog explores the theoretical foundations of MI, critically examines its scientific standing, and—most importantly—demonstrates how it can be contextually and responsibly applied to curriculum design in a way that is student-centered, inclusive, and pedagogically meaningful.

Understanding Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences

First proposed in Frames of Mind (1983), Gardner’s theory challenged the dominance of general intelligence (“g”) by arguing that individuals possess multiple forms of intelligence that reflect different ways of processing information and solving problems. Gardner defined intelligence as a “biopsychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products of value” (Gardner, 2000).

Originally, Gardner identified seven intelligences, later expanding the list to eight, with a tentative ninth:

- Linguistic

- Logical–Mathematical

- Visual–Spatial

- Bodily–Kinesthetic

- Musical

- Interpersonal

- Intrapersonal

- Naturalistic

- Existential (proposed)

Importantly, Gardner emphasized that everyone possesses all intelligences, but in different profiles shaped by genetic, cultural, and experiential factors. Rather than categorizing individuals into fixed types, MI describes patterns of relative strengths and preferences.

Moving Beyond IQ: Why MI Resonates in Education

Traditional educational systems tend to reward linguistic and logical-mathematical competencies—reading, writing, memorization, and numerical reasoning. As Gardner himself noted, these modalities are most valued in schools and formal assessments, often marginalizing students whose strengths lie elsewhere.

MI theory resonated strongly with educators because it:

- Validates diverse learner strengths

- Challenges deficit-based views of ability

- Encourages inclusive and differentiated instruction

- Aligns with student-centered pedagogies

In culturally diverse and resource-variable contexts—such as many Global South education systems—MI offers a framework that recognizes contextual intelligence, including social navigation, creativity, and environmental awareness.

The Eight (and a Half) Intelligences: Strengths in Context

Rather than reiterating definitions, it is useful to consider how each intelligence manifests in real learning environments.

Linguistic Intelligence

Students strong in linguistic intelligence excel in reading, writing, storytelling, and persuasion. In classrooms, they thrive through debates, reflective writing, presentations, and narrative-based assessments.

Logical–Mathematical Intelligence

These learners excel at reasoning, pattern recognition, and problem-solving. They benefit from inquiry-based learning, experiments, data analysis, and structured problem sets.

Visual–Spatial Intelligence

Visual thinkers process information through images, diagrams, and spatial relationships. Mind maps, infographics, models, simulations, and design-based tasks support their learning.

Bodily–Kinesthetic Intelligence

These learners understand best through movement and hands-on activity. Role-plays, lab work, building models, sports-based analogies, and physical demonstrations are particularly effective.

Musical Intelligence

Musical learners are sensitive to rhythm, pitch, and sound patterns. Learning through songs, rhythm-based mnemonics, sound analysis, and creative composition can enhance engagement.

Interpersonal Intelligence

Socially attuned learners excel in collaboration, communication, and leadership. Group projects, peer teaching, discussions, and conflict-resolution tasks suit this intelligence.

Intrapersonal Intelligence

These learners are introspective and self-aware. Journals, self-paced projects, goal-setting exercises, and reflective assignments support their strengths.

Naturalistic Intelligence

Naturalistic learners recognize patterns in nature and environmental systems. Fieldwork, classification tasks, ecological projects, and sustainability-focused learning are effective.

Existential Intelligence (Proposed)

Although less formally accepted, existential intelligence reflects sensitivity to meaning, ethics, and “big questions.” Philosophy, ethics discussions, social justice debates, and future-oriented inquiry often engage these learners.

Designing a Student-Centered Curriculum Using MI

A key promise of MI is that an entire curriculum can be designed to engage multiple intelligences, allowing students to discover how they best understand and express knowledge.

Step 1: Identify Core Learning Objectives

Curriculum design should always begin with clear academic goals. MI does not replace content standards—it offers multiple pathways to achieve them.

For example:

- Objective: Understand photosynthesis

- MI pathways: diagrams (visual), experiments (kinesthetic), group explanation (interpersonal), reflective summary (intrapersonal), song creation (musical)

These examples illustrate pedagogical application rather than claims about cognitive structure.

Step 2: Map Activities Across Intelligences

Rather than matching one student to one intelligence, effective MI-based curricula offer diverse activities within a single lesson or unit.

This pluralization encourages:

- Deeper understanding

- Cognitive flexibility

- Transfer of learning across domains

Step 3: Provide Choice and Autonomy

Allowing students to choose how they demonstrate learning—through writing, presentation, art, performance, or design—enhances motivation and ownership.

Choice does not reduce rigor; when aligned with clear rubrics, it can increase cognitive engagement.

Step 4: Diversify Assessment Methods

MI-informed assessment moves beyond a single exam format. Portfolios, performances, projects, and presentations can assess both content mastery and applied skills.

Research shows that varied assessment methods provide a more accurate picture of student learning (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

Multiple Intelligences Is NOT Learning Styles

A critical clarification is needed: Multiple Intelligences should not be conflated with learning styles.

Learning styles theories suggest that individuals learn best through a single preferred modality (e.g., visual or auditory). Extensive research has shown that matching instruction to learning styles does not improve learning outcomes.

Gardner himself warned against this misinterpretation. MI does not claim that students should only learn through their strongest intelligence. Instead, it argues that learning is enriched when material is presented in multiple ways.

Scientific Criticisms and the “Neuromyth” Debate

Despite its popularity, MI theory faces substantial criticism from cognitive psychologists and psychometricians.

Key Critiques

- Lack of strong empirical evidence supporting independent intelligences

- Overlap with talents, abilities, or personality traits

- Continued support for a general intelligence factor (“g”)

- Difficulty operationalizing and measuring MI scientifically

Some researchers have labeled MI a neuromyth, arguing that it is widely accepted despite insufficient neuroscientific validation (Waterhouse, 2023).

A Balanced Perspective

While MI lacks the psychometric rigor of IQ models, it was never intended as a testing framework. Gardner positioned MI as a theoretical and educational lens, not a diagnostic tool.

some neuroimaging research (e.g., Shearer, 2020) suggests partially distinct neural networks associated with different cognitive domains, offering some support—though not definitive proof—for Gardner’s ideas.

Why MI Still Matters: Educational and Therapeutic Value

Even critics acknowledge that MI has influenced education in constructive ways:

- Encouraging pedagogical diversity

- Reducing deficit labeling

- Supporting strength-based approaches

- Promoting inclusion and engagement

Beyond education, MI has shown promise in therapeutic contexts. Pearson et al. (2015) found that incorporating MI activities in counseling enhanced therapeutic alliances, increased client self-awareness, and expanded counselors’ intervention strategies.

Implications for Modern Learning Environments

In a world shaped by rapid technological change, economic uncertainty, and diverse learner needs, rigid definitions of intelligence are increasingly inadequate.

MI supports two critical educational principles:

- Individuation: recognizing that learners differ

- Pluralization: teaching concepts in multiple ways

Technology now enables scalable personalization through multimedia resources, adaptive platforms, and project-based learning—making MI-inspired pedagogy more feasible than ever before.

Conclusion: Using MI Responsibly

Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences is not a scientifically settled model of intelligence. However, when used responsibly, it remains a powerful educational framework.

MI should not be used to label students, predict ability, or replace evidence-based instruction. Instead, it can serve as:

- A guide for curriculum design

- A tool for inclusion

- A catalyst for pedagogical creativity

- A framework for helping students discover how they engage with learning

Ultimately, the value of MI lies not in proving that there are eight or nine intelligences, but in reminding educators that human potential is multifaceted, contextual, and far richer than any single score can capture.

References

- Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the classroom (3rd ed.). ASCD.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Performance counts: Assessment systems that support high-quality learning. Council of Chief State School Officers.

- Davis, K., Christodoulou, J., Seider, S., & Gardner, H. E. (2011). The theory of multiple intelligences. In R. J. Sternberg & S. B. Kaufman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp. 485–503). Cambridge University Press.

- Edutopia. (2013, March 8). Multiple intelligences: What does the research say? https://www.edutopia.org/multiple-intelligences-research

- Gardner, H. (2000). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. Hachette UK.

- Gardner, H. (2011a). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences (30th anniversary ed.). Hachette UK.

- Gardner, H. (2011b, October 29). The theory of multiple intelligences: As psychology, as education, as social science. Address delivered at José Cela University, Madrid, Spain.

- Gottfredson, L. S. (2004). Schools and the g factor. The Wilson Quarterly, 28(3), 35–45.

- Orfield, G., & Kornhaber, M. L. (2001). Raising standards or raising barriers?: Inequality and high-stakes testing in public education. Century Foundation Press.

- Pearson, M., O’Brien, P., & Bulsara, C. (2015). A multiple intelligences approach to counseling: Enhancing alliances with a focus on strengths. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(2), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038881

- Shearer, C. B. (2020). A resting state functional connectivity analysis of human intelligence: Broad theoretical and practical implications for multiple intelligences theory. Psychology & Neuroscience, 13(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000186

- Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, S. B. (Eds.). (2011). The Cambridge handbook of intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Visser, B. A., Ashton, M. C., & Vernon, P. A. (2006). Beyond g: Putting multiple intelligences theory to the test. Intelligence, 34(5), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.02.004 (doi.org in Bing)

- Waterhouse, L. (2006). Inadequate evidence for multiple intelligences, Mozart effect, and emotional intelligence theories. Educational Psychologist, 41(4), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4104_1 (doi.org in Bing)

- Waterhouse, L. (2023). Why multiple intelligences theory is a neuromyth. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1217288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1217

Test Your Knowledge!

Click the button below to generate an AI-powered quiz based on this article.

Did you enjoy this article?

Show your appreciation by giving it a like!

Conversation (0)

Cite This Article

Generating...